![]()

![]()

![]()

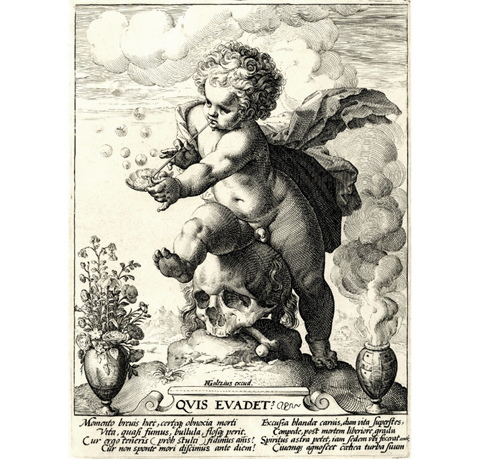

Hot Air | Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield | 1993 | above: Hendrick Goltzius Boy Blowing Soap Bubbles [1594]

< 1 of 9 >

HOT AIR - Mappin Art Gallery - Robert Clarke 1993

The

scene is set by two small wall-based constructions, both using clay pipes,

abutting the gallery entrance. In the first piece glass bubbles swell

from the bowls of two pipes set against neatly painted pink squares. On

one bubble is engraved the word NIHIL (Nothing) and on the other NON NIHIL

(Not Nothing). Whether NON NIHIL is a hint of defiant optimism or an awful

double negative is left deliberately and tantalisingly uncertain by the

artist, Jonathan Allen.

One historical source for the work is Henrick Goltzius's 16th century copperplate engraving, Boy Blowing Soap Bubbles, one of the earliest representations of human breath in Western art. Goltzius's image fits into the Vanitas tradition of 16th and 17th century allegory called Homo Bulla ('Man is a Bubble'). A cute bubble blowing putti, which itself could be the very figure of childhood wellbeing, is seen precariously balancing astride a mouldy looking skull. On one bubble, to underline the underlying emptiness and futility of everything, is written the word Nihil. Allen's reinterpretation gives the memento mori image an extra ironic twist by the addition of the extra negative. Even when desperately aware of the one certainty of human existence, our own mortality, our bodies, relentlessly breathing away, tempt us to deny that certainty, kid us into carrying on as if death didn't really exist.

In the

second construction, the clay pipe, its bowl cupped in the hollow of a

clam shell and submerged in a tank of water, periodically emits a gurgle

of air. One is immediately intrigued by where that bubble of air, that

tiny but elemental sign of life, is coming from. Allen, who employed a

professional magician-craftsman to construct this piece, has been fascinated

with theatrical sleight of hand since childhood. He often makes references

in his work to the world of conjuring and trickery. His last exhibition,

Landscapes of Risk, included for instance one piece entitled Shallow Breaths,

Beating Hearts, showing mysterious details of high wire acts. When all

the more high falutin Post Modernist gang are going on about chaos theory,

alchemy and archaeology, Allen concentrates on a discipline at the same

time more banal and more apparently marvelous than all these - fairground

magic. He speaks not surprisingly lovingly of Wim Wenders' filmic hymn

to a lost but retrievable sense of wonderment, Wings of Desire. On meeting

the artist in the gallery, he sat me down and showed me a card trick as

the quickest way of introducing the thoughts behind the show.

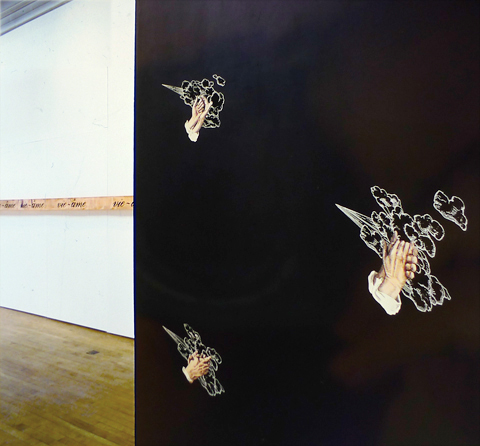

From these scene-setters the show moves out in a circle to play further on ambiguity and ambivalence. One entire long wall is taken up by an unrolled sheet of copper shim on which are silk-screened repeatedly the words ‘vie-âme’. The words are taken from a passage in Gaston Bachelard's Air and Dreams: 'We will hear these words pronounced as we breathe, before we even think about them: vie (life) and âme (soul) - vie as we breathe in; âme as we breathe out.....A day whose rhythm is marked by the breathing of vie-âme, vie-âme, is one that will be in tune with the universe....Beautiful aerial images vitalise us'.

In Allen's installation the words are irregularly spaced to imitate the quickening of breath brought on by a shock of strong emotion. In his research Allen came across references to a series of experiments, conducted in the 1920's, in which groups of women were shown photos of Valentino and the rhythm of their presumably suddenly excited breathing recorded on a pneumograph. The formal stretching of the thin copper roll along the wall itself tells how the punctuation of time by one's virtually silent breathing can speak an age old language.

In the Mappin Gallery's end wall neoclassical apse Allen has created a towering installation. Against a night dark background is set a pattern of innumerable images of hands cupped together amidst illustrated drafts of human breath. One is reminded again of dear old ex-Columbo's touching evocation of this warming gesture in Wings of Desire. The way the images are portrayed however in mock Renaissance engraved hatching once again suggests a melancholia with a longer historical and cultural credential.

Allen is an artist more happy to be seen working in the British Library than in any more typical pseudo romantic remote mountainous region, near derelict warehouse or backstreet dive. Having taken on the subject of air and breath his research has been extensive and impressively comprehensive taking in contemporary and historical visual art, poetry, philosophy, political history and the medical sciences. He will follow the haunting images of suspense in The Experiment with The Air Pump by the 18th century painter Joseph Wright of Derby through to a 1691 treatise The General History of the Air by Robert Boyle, the air pump's inventor. The contextual source material for the Hot Air show, partly represented in the exquisitely designed and printed catalogue, ranges from assemblages by Man Ray, Duchamp and Manzoni historically back through J G Frazer's The Golden Bough to Shakespeare and El Greco. Allen followed the research trail to some unlikely sources. For information on historical references to breathing he wrote to Dr. George W Scott of Guy's Hospital who replied with a 1879 textbook description of the sound of a pneumonia sufferer's breathing: 'Fine crepitations have been likened to.....the explosion of a maroon rocket bursting suddenly into a shower of crackling and brilliant stars'.

The visual and conceptual feel of the work overall is somehow reminiscent of that aspect of Renaissance culture which enabled an artist to be an explorer in an array of creative research and inventive disciplines, a level of simultaneous involvement inconceivable since the Industrial Revolution introduced the division of labour. Allen points out however that the capacity to peruse numerous fields of knowledge by computer is now so great that there's no reason why artists today can't revel in the same 'confusion and excitement' as their Renaissance forebears.

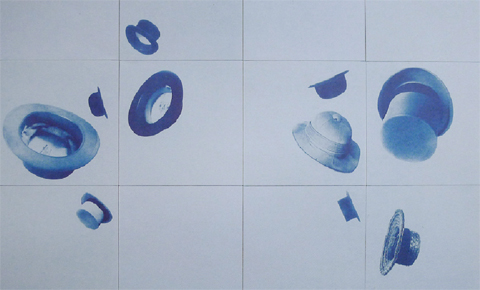

It must be said that Allen's work doesn't give the impression he's laboured over all this research so much as delighted in it. Once he alights on an appropriate image from whatever historical source, he adapts it to his overall theme with an acute eye for the poignancy of poetic juxtaposition. From the work so far mentioned, painfully sensitive as it all is to ephemerality and mortality, he goes on to picture a petrified moment of magic. On a recent visit to Russia the artist happened across a late 19th century watercolour showing a group of figures cheering heartily and flinging their hats in the air. From his memory of this tiny painting, he has restaged in the form of a large blueprint photograph, a close-up image of flung hats thus set at the apex of their flight as if the scene is caught in the split second held breath between spontaneous celebration and the inevitable return to self consciousness.

Some times he even mischievously infiltrates his historical references with a self-invented mock history. One particularly intriguing section of Hot Air has the recorded last words of various famous figures etched onto glass discs which project from the gallery wall. When one looks more closely however the factual basis of some of the names and quotes are cast in doubt. The piece comes across with a rare poetic and enigmatic concision. Some last gasps include: Emily Dickenson 'I must go, the fog is rising'; Francoise Rabelais 'I go and seek the great perhaps'; Richard Sheridan 'I'm absolutely undone and brokenhearted'; Paul Verlaine 'Don't sole the dead man's shoes yet'; Marion Crawford 'I love to see the reflection of the sun in the bookcase'.

Thus Allen might use found objects, texts and images but they neither simply court the dadaist disorientation of Duchamp nor the cool Pop detachment of Warhol. Allen's treasure trove of evocative found objects of historical significance are juggled with gleefully. He sets his found treasures against each other to catalyse questions, to spark off not so much the weirdnesses of dream as the open ended wonderments of philosophical speculation.

[Robert Clarke, June 1993]

![]()

HOT AIR [1993]

publication ISBN 0952118106

supported by the Henry Moore Foundation and designed by

The Workshop, Sheffield

Photography

Mark Enstone

All works © Jonathan Allen 2012. All photographs are © their respective authors.